South Pass. One of the western world’s most promising big game fishing spots and only 100 miles from the foot of Canal Street.

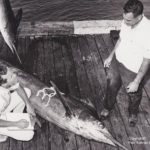

If he breathes deeply, stands very straight in his Topsiders. and stretches himself to maximum height, Clyde V. Hawk just manages to reach five feet five. This is precisely seven feet three inches shorter than the giant blue marlin which occupies the place of honor in the ornate trophy room of Mr. Hawk’s Canal Boulevard home. In its un-taxidermied state, the marlin weighed 508 pounds, making it one of four blue marlin over 500 pounds to be captured intact (without shark bites) from Louisiana waters.

Besides the 508 pounder, the diminutive Mr. Hawk has taken one other specimen weighing 500 pounds even, plus 38 more blue marlin whose average weight ranged well in excess of 300 pounds, a most remarkable accomplishment which places Mr. Hawk in the lead for catching more blue marlin than any other Louisiana angler. By way of contrast. Harley Howcott ranks second with his lifetime record of 36 blues while Dr. James W. Burks, Jr. is third with 18.

Particularly noteworthy to Crescent City anglers is the fact that with the exception of three marlin Mr. Howcott caught off San Juan. Puerto Rico and one that Dr. Burks subdued near Fort Lauderdale, all of the aforementioned action took place approximately 100 miles from downtown Canal Street in an area acclaimed as one of the most promising big game fishing hotspots of the western world.

From mid-May until the first chilly blasts of late October. South Pass of the Mississippi River becomes second home to Messrs. Hawk, Howcott. Dr. Burks, and a fast-growing army of equally dedicated sportsmen who share the delightful misfortune of having been bitten by the big game fishing bug.

The presence of genuine bragging size fish so close to New Orleans is nothing really new or surprising because they have been there for thousands of years. It is simply that people did not display much interest in going after them until fairly recent times. Isolated instances of billfish being brought into nothern Gulf of Mexico ports in yesteryear caused some commotion, to be sure, but any truly serious efforts to capture such monsters could almost be counted on the fingers of one hand.

These early forays entailed a definite margin of risk insofar as tire participating anglers had only the haziest notion of where they were going, whether the boat would hold together for the full duration of the voyage, or what they would encounter once they arrived where the water becomes unbelievably blue and deep. The author knows this to be true because he signed on for quite a few of these pioneering expeditions.

One of my most memorable ice-breaking experiences occurred in the company of Jack Brown, a highly individualistic man who was and still is the sharpest charter boat captain I have ever known. During the summer of 1949. I was writing the fishing column for the old New Orleans Item and working weekends as an un-paid deck hand aboard Jack’s charter cruiser “Sea Hawk” out of Grand Isle. In addition to notes for my column, I picked up considerable addenda about navigation, rigging baits, and soothing seasick passengers. For this particular trip. Jack decided to forego the charter fee and leave all paying guests ashore so we could fish as active participants in the Grand Isle Tarpon Rodeo.

On opening day. we captured the first, second, and third prize jewfish. several very sizeable tarpon, and a tackle busting cobia. but Jack insisted that we also seek top honors for the heaviest dolphin. The biggest dolphin in the rodeo record book at that time weighed only about eight pounds and was also the official record for Louisiana waters.

Jack and I drove “Sea Hawk” more than 50 miles offshore into the shipping lanes where the sea was the color ol purple ink. We located several large patches of Sargasso weed and proceeded to stand the Grand Isle Rodeo on its historic ear by hauling in a dolphin weighing 23 pounds. I snagged an even bigger one but it threw the hook on the first jump.

The loot we came home with was positively disgraceful. In addition to a new Plymouth automobile, we won a complete set of auto tires, several outboard motors, and enough fishing gear to open a sporting goods store. This was incidentally, the last time that charter boatmen were allowed to compete in the Grand Isle Rodeo.

Before our adventure, an odd and occasional sailfish had been hauled into Grand Isle. One of the earliest Louisiana sails I can recall was caught aboard the old two-masted schooner “Flying Dutchman” which also worked in the charter trade.

For all intents and purposes. Louisiana big game fishing remained in embryo condition until the early 1950s when the United States Fish and Wildlife Service instituted a series of investigational voyages aboard the research vessel “Oregon” which was assigned to study the feasibility of fishing for tuna on a commercial basis in the Gulf.

“Oregon” experimented with several types of commercial fishing gear but made her biggest catches on a device known to the trade as the Japanese long line. This was nothing more than a king-sized trot line carrying several hundred hooks suspended from a rope almost two miles long. Tire gigantic line caught fish in numerous places from the north coast of Cuba down into the Bay of Campeche but some of “Oregon’s” most impressive hauls were realized a short distance out from the Mississippi Delta where the Continental Shelf comes closer to shore — 11 miles — than at any other point in the entire Gulf of Mexico. Here, the take included not only the delicious white-meat Allison or yellowfin tuna but surprising numbers of blue marlin, white marlin, and sailfish plus an occasional Mako shark, swordfish, or other equally exotic species.

This proved what some of us had long suspected. In the days before World War II when we fished for tarpon every summer weekend at Southwest or South Pass, I would delight in listening to the tall tales spun by Johnny Mathes. Warren Ebrenz, Edouard Morgan. Herman Deutsch. Lester Lautenschlaeger. and Miles Pratt about how they hoped to someday explore the deep waters far offshore. Jack Brown, of course, had precisely the same thing in mind when we caught the first big dolphin.

My infatuation with South Pass became most severe one evening in early June 1956 when I invited Haney R. Bullis Jr., chief of the “Oregon’s research party, to drive over from his Pascagoula laboratory and appear as a guest on my Jax Beer “Outdoors in Louisiana” television show. Harvey brought with him some of the movie footage he had made showing the long line in action and the sight of marlin and tuna being hauled aboard the “Oregon” hand over fist was enough to give me the cold sweats.

Harvey’s visit erased forever any doubts I may have had about South Pass but simply intensified the very serious problem of transportation. The boat I owned, a 16-foot outboard hull, was scarcely big enough to run the Mississippi much less the open Gulf. It occurred to me that some of my friends among the Grand Isle and Southwest Pass tarpon fishing fraternities owned substantially bigger boats and might be interested in joining an exploration tour of the fabulous new waters. I began making phone calls. The first three men I contacted agreed to have lunch with me at Arnaud’s Restaurant where we worked out the details. They included James Meriwether Jr. of Shreveport. owner of a 65-foot steel yacht named “Melou II”. Bob Norman of New Orleans who owned a 36-foot Chris Craft called “Kiwi,” and John Lauricella Sr. of Jefferson Parish, father of former Tennessee football great Hank Lauricella. John’s yacht-rigged lugger was aptly christened “All American.”

Not one of the vessels had outriggers, flying bridges, fighting chairs, or any of the niceties which are considered de rigueur by today’s big game fishing standards. In addition to these deficiencies, nobody but Lauricella nor I had any previous experience with giant fish. I had caught a few sail fish in Acapulco, a pair of black marlin in Panama, and had boated bluefin tuna in the Bahamas and at Wedgeport, Nova Scotia. Lauricella had snagged several sailfish off Grand Isle while fishing for tarpon. We pooled our meager knowledge about rigging hooks, leaders and baits and shared it with our friends. Bob Norman had a new captain on the “Kiwi” and asked me to round out his crew.

Before leaving New Orleans. I contacted Jack Styron at Wallace Menhaden Products and arranged for him to have two drums of “pogies” set aside for us at his plant in Empire, my thought being to use the menhaden for chumming in a manner similar to the way I had seen it done for bluefins in Nova Scotia. Only when we picked them up in Empire did I discover that the chum was 36 hours old, had mellowed in the hot June sun, and smelled to high heaven. The faisande menhaden were placed delicately in a skiff and towed astern of the “Kiwi” on a very long line. Upon reaching Port Eads, we anchored the reeking tender a discreet distance downwind from our dockage.

That evening. Signor Lauricella issued a blanket invitation for us to imbibe in a classic Neopolitan feast starting with stuffed artichokes and scampi and working its way through every Italian delight known to man. Heady Marsala wine was quaffed in 16-ounce iced tea glasses. I realized it was too much when I downed my fifth pony of Stregga at 2 A.M. and watched the hands of the ship’s clock go spinning around.

It was a miracle that any of us could get out of bed the next morning. Nevertheless, we arose before dawn to be greeted by a nasty East wind kicking up the Gulf. Bobby couldn’t attempt towing the skiff in such seas so we transferred the menhaden into the “Kiwi” Thus did our tiny armada embark upon its epic voyage with stately “Melou II” leading the way, “All American” next, and “Kiwi” bringing up the rear with a peculiar blue haze trailing behind her.

The monotonous roar of “Kiwi’s” engines blended with the gentle rocking of the waves to lull me fast asleep in a deck chair, absolutely oblivious to the presence of the rotting fish. Only when we approached the tidal “rip” and blue water did I discover that I was violently sick to the stomach. Fighting back an urge to lie down on the deck and die, I quickly rigged a couple of mullet baits, tossed them overboard, and raced for the railing.

In a matter of seconds, my reel started screaming like a love-starved alleycat. My first impulse was to grab the rod and fight the fish. I realized, however, that my tormented condition would permit no such exercise so I invited Bob to do the honors.

Thus, did Robert Norman become tile first person ever to take a tuna from Louisiana waters on sporting tackle.

At this point, we relieved “Kiwi” of her foul cargo by giving the menhaden the deep six. “All American” started trolling around an oil slick left by the menhaden and hooked into a white marlin, just as this fish was being boated. I hooked another of identical size. This put John Lauricella on history’s scoreboard with Louisiana’s first rod-and-reel-caught marlin and me with the second.

After chat, an amberjack and a trio of king-sized dolphin were nothing but icing on an already elaborate cake.

Jerry Touchy reported our accomplishment in the June 26. 1956 edition of the New Orleans Slates, triggering an un-expected invasion of boats from New Orleans and Grand Isle. The most notable member of this group was a popular Grand Isle charter boat skipper. Bob Mitcheltree, who had visited South Pass in April of the same year when he drew a complete blank. Bob told me later that he encountered high winds and surmised that he didn’t go far enough offshore to overcome the influence of a high river. He returned in May when he caught a boatload of dolphin and struck what seemed to be a bluefin tuna which bent his hook.

The keel for Bob’s “Jennifer Ann,” a slow but sturdy Bayou Lafourche lugger, was laid down at the same time “Oregon” was doing her original investigative work and Mitcheltree’s avowed purpose in building the vessel was to use her for big game fishing.

Immediately following our initial marlin and tuna strike, Mitcheltree returned to South Pass for the third time with a charter party headed by Harley How-cott, an experienced big game angler from New Orleans. They boated several sailfish but failed to see a marlin.

Mitcheltree was living in Grand Isle and fishing occasional South Pass charters when one of his regular customers. Dr. Glenn Gibson of Baton Rouge, succeeded in boating the first blue marlin on June 21, 1958. It weighed only 180 pounds, rather puny by present day standards, but it was the first of its species to be caught on sporting tackle in Louisiana waters.

Less than one week later. Jim Meriwether caught a 463 1/2 pounder which held the state’s marlin record for more than five years. I was aboard the boat “Number 58” trolling right alongside Meriwether’s “Melou II” and had the pleasure of making photographs as the big fish put on a spectacular aerobatics display.

YELLOW FIN TUNA comes aboard charter boat “Holliday” following grueling battle. Such prized fish abound in teeming waters off South Pass.

Meriwether was using the finest tackle money could buy but his yacht was too big and slow for this kind of fishing. After wearing down the marlin until it was completely dead. Jim was horrified to find that the yacht’s sides were too high for his fish to be lifted into the cockpit. He might have hoisted the marlin up on a gin pole except there was none, a deficiency he rectified two days later.

Clyde Weeks and his brother Carleton. Jim’s professional captain and mate, were forced into a maddening race to keep the marlin from being devoured by sharks. Jim emptied a full box of 30 caliber cartridges into the marauders while Clyde tail-roped the marlin, got another line around the head, and secured the bulky carcass to the transom. Jim vaulted to the bridge, opened the throttles, and wrecked two fine engines by operating them at full speed for the long trip back to Grand Isle.

For the next three years. Bob Mitcheltree went through the standard chores of a Grand Isle charter captain, but his mind wasn’t on his work.

“It’s kind of hard.” he confessed, “to fish for marlin and tuna and then go back to trolling for Spanish mackerel. I took it as long as I could. Finally, in May of 1959, I told my wife Jessie I couldn’t stand the strain any longer. I was wearing out both my boat and myself trying to ‘commute’ all the way from Grand Isle. So, we rented our house on the island, packed our gear aboard the “Jennifer Ann”, and let down our roots permanently at the mouth of the river.”

Mitcheltree’s South Pass headquarters was a ramshackle cottage which he purchased from a carpenter who had done work for the Corps of Engineers. It was appropriately named “River’s End” and quickly became a mecca for any and all anglers visiting Port Eads. The makeshift wharf which served as a veranda was the scene of lively gatherings where weary anglers would sip their Scotches and Martinis and talk into the night.

“River’s End” could accommodate less than a dozen anglers. The others ate and slept aboard their boats tied up at the adjacent lighthouse station operated by the Coast Guard. At all hours, they would be forced awake to tighten and loosen moorings to compensate for wave wash from passing ships. The absence of fuel, fresh water, and ice added to their problems. Until 1962 when the Plaquemines Parish Commission Council established a fueling station, fishing boats had to carry aboard every drop of gasoline or diesel oil they would need or else refill their tanks 2-1 miles upriver at Venice. Even today, potable water remains a vital consideration. Except for what can be caught in cisterns, water must be barged to Port Eads and dispensed with appropriate care.

On September 28. 1961, the Coast Guard automated the light station, moved its men to another base at the Head of Passes, and turned over the property on long term lease to Plaque-mines Parish. Captain Mitcheltree was appointed custodian of the 328-foot wharf, a warehouse, and the four former Coast Guard houses. He pumped gas. sold bait, and continued operating ‘Jennifer Ann” until 1965 when he decided to retire. The present custodian. Roe Giordano, is also in charge of letting out slips in the new marina where more than 100 boats arc accommodated on a first-come, first-served basis. All Port Eads facilities, with the exception of the clubhouse, are open to the general public.

To backtrack a bit. the Winter of 1960-61 looms large as the most important turning point in South Pass history. I first became aware of what was happening when I answered a phone call during the Christmas holidays from Herman Prager Jr., a local machine shop operator whom I knew somewhat vaguely as a power boat racer. I had originally crossed paths with Prager in 1956 when he was Commodore of the New Orleans Power Boat Association and I was covering the Pan American Regatta for Yachting magazine.

Herman wanted to come over to my house so he could discuss some ideas for organizing a fishing club. He explained that he had been fishing a few times with Mitcheltree, had become enamored of the sport, and wanted to see if he could activate some kind of group to promote this type of fishing.

I spent most of a Saturday afternoon telling Herman everything I know about big game angling in Louisiana and elsewhere and gave him the names of some 20 men whom I felt had the necessary qualifications for his organization. Several of these, including Lauricella and Norman, were members of the elite but defunct Club Atlanticus which the late John Letellier. Jimmie Rutter, and a few other friends had put together some years earlier to conduct private tarpon and redfish rodeos. Charlie Degan, the retired assessor and a charter member, recalls that Club Atlanticus started off with eight boats in its fleet but that “it finally grew too big and eventually went under.”

The first two men on the list I gave Prager were Leander H. Perez. Jr. and Major General Raymond Hufft whom I knew for many years through my association with the original Southwest Pass Tarpon Rodeo. Hermann Deutsch had started this tournament before World War II and passed its supervision over to me when I became outdoors editor of the Item. Dr. William A. Wagner and Dr. Don L. Peterson, two more ardent tarpon anglers, were also on the list along with Dr. Jim Burks. Harley Howcott and Richard Freeman, all of whom played important roles in the early development of South Pass.

Prager issued the necessary invitations and scheduled the New Orleans Big Game Fishing Club’s first meeting on May 25. 1961 in the trophy room of the New Orleans Athletic Club. To the 21 men attending. Prager reported that he had received 33 applications with 27 people making the $50 deposit toward membership. A decision was reached to limit the club to not more than 50 members. One month later. Prager was elected president. General Hufft vice-president, attorney Gordon Hyde was named secretary-treasurer, and Lea Perez. Jr. occupied the post of “tournaments chairman.” This same slate of hard working officers has been unanimously re-elected every year.

Harley Howcott and the writer were authorized to perform an exhaustive study of the angling rules of several older, longer established groups such as the Catalina Tuna Club and the Miami Rod and Reel Club and to draft a set of fishing regulations. Howcott, a proper, precise, and urbane gentleman from the old school, is in addition to being a superb angler, owner of the city’s most extensive collection of books dealing with the subjects of fish and oceanography.

In its original statement of intentions, the New Orleans Club avowed “to further and promote conservation of marine fishes … to keep the sport of marine game fishing ethical by adhering to the rules of the International Game Fish Association, to encourage this sport both as recreation and as a potential source of scientific data, to keep up-to-date charts of these fishes . . . relative to their capture or release, and to further evaluate and publicize the potential of big game fishing off our Louisiana coast.”

In February 1962, arrangements were made for the club to occupy one of the vacated Coast Guard cottages known as the “Number Four Building.” The facility was operated on a do-it-yourself basis with every member handling his own cooking and housekeeping.

From this point, the development gained speed. On March 22, Plaquemines Parish brought in two 17,000-gallon fuel tanks, one for gasoline and the other for diesel, and purchased a generator to provide electricity. At the beginning of Summer, the Louisiana Land and Exploration Company dredged a slip to harbor their houseboat outside the mainstream of the river’s current and conveniently made it big enough to accommodate 24 sport fishing boats.

The club’s first tournament was held over the July Fourth weekend of 1962 and attracted 46 members and 44 guests. It has always been a rule that members and guests roust fish in separate divisions. Likewise, the club traditionally refers to its gatherings as “tournaments” rather than “rodeos.”

From its beginning, the club has been popular with the medical and dental professions. Out of the present membership of 117, 12 are physicians and three are dentists. The seven-man board of directors screens candidates for membership and rules on all applicants. An un compromising code dictates that members must at all times conduct themselves like gentlemen under penalty of fine or dismissal. One former member who acted out of turn during a tournament had the riot act read to him and has never been heard from again.

This insistence on exemplary behavior is reflected in the large number of wives who accompany their husbands to South Pass. Some of the women are truly devout anglers, others don’t want to sit home as fishing widows, while still a few others find it fashionable simply to be seen amid the affluence and glamour that form an integral part of big game angling.

Whatever else it might be, marlin and tuna fishing definitely is not a recreation for ditch diggers and ribbon clerks. The overall cost of catching a single blue marlin is variously estimated around $10,000 and some fishermen go for years without making a single kill. General Hufft was one such angler who was “always a bridesmaid and never a bride.” Fishing relentlessly for more than five years without boating a blue. When his losing streak was finally broken several seasons ago, the General cut loose and captured three big marlin in quick succession.

Those who wish to participate in the sport have the option of buying their own boat and equipment or hiring one of the handful of charter boats that work out of Port Eads. There are things to be said in favor of both methods. While the ultimate decision is mainly based on finances, virtually no way exists to go big game fishing without spending considerable sums of money. For example, it cost not less than $165 per day to hire a suitably outfitted charter vessel, excluding shore accommodations which run from $15 to $30. A private boat owner can expect to invest anywhere from $5,000 for a single engine 20-footer to more than $100,000 for a 45-foot air-conditioned diesel powered cruiser equipped with radar. On top of this, he must figure in fuel, insurance, dockage charges, depreciation. and up-keep which often amounts to 25 percent of his initial investment.

Still another expenditure must be made for tackle. While charter boats generally provide the gear at extra cost, most South Pass regulars have at least one and usually more Tycoon rods (average cost $250) and Fin/Nor reels (cost upwards of $800). Silver mullet baits flown in from Miami are priced from 75 cents to $2.50 apiece, depending on whether the fishermen wants them already rigged with hooks and leaders or knows how to do this himself

Casual visitors are accommodated aboard two air-conditioned houseboats moored in the Port Eads marina. One of these is operated by veteran charter skipper ”Happy” Morse who was living aboard in 1965 when Hurricane Betsy-struck.

Morse and an elderly cook huddled in terror on the second floor as the “Elbe Susan” slipped her moorings and raced 20 miles across East Bay before finally running aground. The entire lower deck was smashed beyond recognition and it was a genuine miracle that the men survived.

The original “Number Four House” was another Hurricane Betsy victim but the late Judge Leander Perez quickly came to the club’s rescue and offered them his personal quarters. In appreciation, the members voted a special assessment which they turned over to Plaquemines Parish’s homeless families with no strings attached. This larger building is now under lease to the club. A full-time management couple, Burl and Aggie Ray. are employed to supervise operation of the sleeping and eating facilities.

As its fame spreads, South Pass attracts growing numbers of distinguished visitors. Last summer, General Hufft and Lea Perez played host to Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland who was then heading allied military operations in Vietnam. Senator James Eastland of Mississippi was a frequent guest of Judge Perez along with Lieutenant Governor C. C. “Taddy” Aycock and a horde of political lesser lights.

District Attorney Jim Garrison fished out of South Pass long before anyone ever heard of Lee Harvey Oswald and almost became a casualty when the compass on his hired boat went awry and steered him far out to sea. With the gas tanks running dry, Garrison got off a distress call that eventually brought rescuers.

Accidents and near-accidents can always be expected around powerful boats, deep water, or big and potentially dangerous fish. When all three are combined, the results are inevitable. South Pass has experienced its share of close calls. One of the most harrowing was that of Dr. Charles Odom, the Jefferson Parish coroner, whose “Little General” hit a submerged log while coming into port full speed with a prize winning blue marlin in the cockpit. The boat went down like a rock but not before Dr. Odom’s professional skipper. Captain Dave Young, was able to establish contact with a nearby Coast Guard cutter. The survivors scrambled aboard the cutter as giant hammerhead and black-tip sharks snapped at their heels.

Sharks, whales, un-identified submarines, and even Cuban fishing boats are not uncommon sights. The sharks are a constant menace, mutilating dozens of fine tuna and marlin every year. Only very stupid people will attempt fishing South Pass without a life raft ready and wailing if the need should arise. The whales are harmless and provide a source of wonderment for newcomers who don’t understand that the northern Gulf of Mexico was one of the nation’s prime whaling centers in the early part of this century. The submarines could belong to any nation because everything outside the three-mile limit is classified as international warn The Cubans are long-liners who take tons of marlin, swordfish and tuna for the Havana market. Fortunately, they seldom, come closer than 50 miles.

Clyde Hawk, who has the yacht ”Holliday” under charter for most of the Summer, takes a view that “you can’t catch fish unless your line is in the water.” The number of marlin Hawk and Burks have caught is testimony to their judgment.

Harley Howcott and his wife, Alice, spend almost all their weekends fishing with “Happy” Morse on his charter boat “Chips V”. flying back and forth from New Orleans in a rented seaplane which gets them to Fort Eads in 45 minutes instead of the customary auto-boat route of 3-4 hours. Howcott was the first man to encourage South Pass anglers to release their catches unless they were in competition or wanted to have the fish mounted. He also established a working arrangement with the Woods Hole Oceangraphic Institute to supply tagging devices to aid in tracing the migrational habits of the fish.

Since 1967. the New Orleans Big Game Fishing Club has cooperated with the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission in sponsoring a scientific survey aimed at uncovering potentially useful information relating to pelagic fishes, their feeding habits, etc. Practically every fish brought into South Pass for weighing is minutely examined by a graduate biologist who takes precise measurements, determines the fish’s sex. and sees what it has been eating. One curious development already uncovered is the fact that 90 percent of all blue marlin caught off South Pass are females. In the Bahamas, the opposite is true of males.

In recent weeks, the author had a hand in conducting an eight-hour course of instruction in basic big game fishing for children whose fathers belong to the New Orleans Big Came Fishing Club or the Southern Yacht Club. Classes were held at the S.Y.C. on Friday evenings and attracted almost three dozen kids who became bug-eyed at the mention of thousand-pound fish, whales, sharks, and similar commentaries which form a everyday part of the big game fishing lexicon.

Once a year, the New Orleans Big Game Fishing Club holds a banquet to cite its champions. Until his death. Judge Perez was a familiar sight at these functions, never attempting to hide the way he felt about the club. He is the only person upon whom the club has bestowed honorary membership.

Expanding interest in big game fishing has spun off a whole succession of new fishing clubs and sources for the yachts, tackle, and bait needed for this highly specialized angling. Dennis and William Good, Jr. two enterprising brothers who caught onto die idea early, parlayed a tiny boat brokerage at West End into a sizeable business that sells hundred-thousand-dollar sport fishing cruisers like they went going out of style. Average delivery time for a 41-foot Hatteras, presently their most popular model with a price tag of better than $70.000. is now almost a year.

It is a sad but accurate commentary that most Johnnies-come-lately arrive at South Pass without the slightest knowledge of what they are doing, relying on the kindness and courtesy of experienced anglers to learn the ropes about making baits, handling gaffs, and even getting back to port. From 40 miles out. the latter task is similar to finding the needle in the proverbial haystack.

Such neophytes would do well to heed a few well-chosen words from Clyde Hawk, a four-time angling champion.

“Patience.” proclaims Mr. Hawk, “is the key word to success in big game fishing. You must learn right from the beginning to accept bad days with the good, knowing that the law of averages will eventually turn in your favor.

“Teamwork and determination are equally important factors. The angler, the mate, and the man handling the boat must all work in absolute harmony or you will never catch fish. Many boats raise prize fish only to lose them because of inexperience or lack of teamwork.

“Certainly, I use a fine boat and a highly trained crew, and this is the reason I have been successful. Captain Bert Smith, my skipper, has eyes like…well, like a hawk. . .and his reactions arc as fast as lightning. The fact that we came in with the first marlin of the season this year and caught the first place blue marlin and yellowfin tuna in the club’s opening tournament is also no accident.

“It is the result of hard work, and just a little bit of luck.”